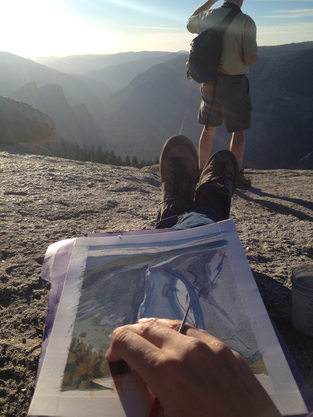

| A couple of weeks ago myself and two of my friends, a photographer and a writer, went on a mission to document the evening up at Sentinel Dome in Yosemite. We each worked in our respective mediums, setting out to capture the valley that has been our home this season. We shared the experience with a dozen others, most of whom were plainly from out of town. But even the drunken guy was exclaiming to his friends how spectacular the view was. I didn't mind it. I know how amazing this place is, but I still like to be reminded that even in the moments when it seems pretty mundane, (not that evening by any means) someone is passing through on their once in a lifetime visit. The disadvantage of my process is that in the two or so hours we were up there, I only left with one image. With only an hour or so of good light I can't spend a lot of time looking at different angles to paint and the 360 degree view from Sentinel Dome proves to be a test of commitment. My choice was to look toward El Capitain, one of the more famous features of the valley and one I somehow had not painted at all this season. Part way through, a "hopefully-so-mesmerized-by-the-sight-that-I-am-unaware-of-my-surroundings" visitor stood in front of me to take his pictures for a few minutes. I tried to appreciate the opportunity it gave me to just look for a little while. |

Here is an excerpt from Roger Minick's 2012 field notes about some realizations he had while photographing his Sightseer series over the course of 30 years. The full website is sightseerseries.com.

"Throughout my hours of driving and time spent at hundreds of overlooks––from Yosemite National Park to the Blue Ridge Mountains, from Old Faithful Geyser to the rim of the Grand Canyon, from Niagara Falls to the St. Louis Arch, from the Crazy Horse Memorial to the World Trade Center, from The Alamo to the Washington Mall, from Zion Canyon National Park to the Great Smoky Mountains––there was one question that continued to press upon me for an answer. What was it that motivated people, by the hundreds of thousands, at great expense of time, money, and effort, to visit these far-off places of wonder and curiosity? I must confess that there were times in my travels, squeezed elbow-to-elbow with my fellow travelers, that I viewed their presence at the overlooks as nothing more than another example of mindless, boorish, behavior. I thought they were there simply to get their pictures taken as quickly as possible, the one tangible validation of their trip, and then head on to the next overlook, the next campground, motel, bus stop, then home––the experience at any one of the dozens of overlooks remembered only later through a snapshot they barely recalled taking.

But in the end I came to believe that there was something more meaningful going on––something stronger and more compelling, something that seemed almost woven into the fabric of the American psyche. I would witness this most dramatically when I watched first-timers arrive at a particularly spectacular overlook and see their expressions become instantly awestruck at this their first sighting of some iconic beauty or curiosity or wonder. After seeing this happen innumerable times, I began to compare what I was seeing to the religious pilgrimages of the Middle East and Asia, where the pilgrims are not just making a trip to make a trip, or simply to return home with some tangible piece of evidence that they were there––the snapshot––they have instead come seeking something deeper, beyond themselves, and are finding it in this moment of visitation. For as with all pilgrimages, they have made the journey, they have arrived, and are now experiencing the quickening sense of recognition and affirmation, that universal sense of a shared past and present, and, with any luck, a shared future."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed