During my first season at Glen Canyon I was exposed to the history of art in the creation and establishment of the National Parks. That it was the painters- Moran, Church, Innes, Catlin, Bierstad- who brought both the image, and more importantly the feeling, that those living in the east needed to feel like they too had seen the grand vistas of Yellowstone and Yosemite, the Grand canyon and the High Desert. Having recently graduated art school I continued this tradition of painting the landscape to send the image home to the east.

While interpreting a petroglyph panel called "The Descending Sheep" for visitors I learned to speak of the simple images of Bighorn Sheep in terms of location, not as language or with the view of an art critic. But I could speak about the process, the resulting image, and the way we could pull some historical details out of them. To me these images were such a part of the landscape it was as if over time the sandstone grew the image to reflect the feeling of the west. The reason behind their creation is unclear, but I have no doubt that the maker's surroundings were important to the process. It is hard not to know that while viewing the panel in it's context along the edge of the Colorado River, at the bottom of the famous Horseshoe Bend.

That same summer I learned the role of art in exploration, that the Dominges Escalate expedition had a painter, and that John Wesley Powell dragged a painter with him on his exploration of the Colorado. (One of my favorite stories is that Powell sent the young painter up a large mountain, nearly the exact same consistency of a sand dune, in order for him to paint the view and bring it back to the rest of the party. If you have never climbed 1,000 feet up a sandhill you should go walk on the soft sand of a flat beach and see how your legs feel after 20 minutes.)

In the last 5 years I have run into musicians 10 miles into the backcountry, dancers in tree groves, sculptures set up in front of elk herds, and figurative drawers and painters doing sketches of the crowds. Not to mention the countless photographers in all manner of weather extremes. No matter what the medium I always appreciate that someone has slowed down to make something of where they are in real time.

During a recent discussion on the merits of art and the parks, specifically on the idea of National Parks putting funding toward individual artists, I came across a few thoughts that I had previously been unable to put into words. Yes, art is often a solitary process. Yes, it is not always easy to integrate it into a park's education program. Yes, to have an employee out teaching a small group the basics of painting may not be as helpful as having another person to answer visitor questions at the desk of the visitor center. But when I considered my experience of painting outside in the busier areas of the parks I thought about the hundreds of conversations I could have a in a couple of hours of painting. The large number of people who were amazed to see someone set up to paint in one location. I was struck by how many people told me that they "used to draw," or "always wanted to paint." I thought of the first time someone shared with my via social media that they started sketching again. And I think about how many people slowed down their frantic rush to see everything to join me in looking at what I was seeing. That they gave me 2 minutes out of their trip to watch my process is a very generous gift of time. If you have never spent time visiting a national park you may not realize the amusement park style movement that is the base of a Yosemite Waterfall, the edge of a vista, or a boardwalk through a Geyser Basin. So while it is hard to put to words the need for artists- I have experienced firsthand how they can enrich the visitor experience.

I have been fortunate to be an artist in residence at three National Parks. The experience at each one was unique, and exposed me to new people, new parts of the country, and took my work in new and exciting directions. I am currently at Weir Farm, one of only a few National Park Service sites dedicated to American Art, and the only one to be dedicated to American impressionism. There is no question here of art's role in the visitor experience. It is a cool November weekend- but from where I sit I can see a painter set up on the grounds for the day.

A sub part of the earlier mentioned conversation was the creation of a list about what National Parks offer artists in the context of the artist in residence program. As you can tell I am a landscape painter. For me the parks are both studio and muse. But for many artists were is a disconnect between parks and the modern art world. For this reason the staff at Weir Farm decided to appoint me a year-long title as Centennial Artist Ambassador. The purpose of this program is to connect artists to the facilities that Weir Farm has to offer, as well as the general promotion of the National Park Service artist in residence programs. I am honored by this opportunity. 2016 is the 100 year anniversary of the National Park Service, and while I will continue my work as a ranger, I am thrilled to be able to dedicate my off-hours to the continued relationship of art making in the public landscape.

If you are an artist who has considered a residency in the parks, or perhaps have never considered one, please send me an email through my contact page. I would be happy to answer any questions or try to help you find a park that suits your medium.

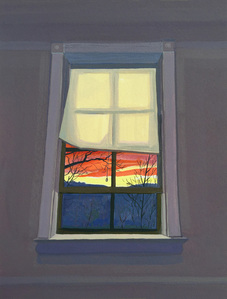

Below is the studio at Weir Farm. It is a recently re-designed facility with high ceilings, Northern light, excellent lighting, and many windows that can be opened to the outside. Weir Farm has a working relationship with The Center For Contemporary Printmaking, which is only 25 minutes away and offers cheap studio rentals to Weir Artists.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed